Sir Isaac Vivian Alexander Richards was a soft and shy man, not an arrogant prince. He lived for the day, while retaining a sense of history. He was not a genius, as Imran Khan thought. The word genius implies a depth of rational thought and consideration, which was never part of Richards' game. He was more an intuitive artist blessed with an exceptional gift for violent performance. A gladiator, perhaps. He was driven by a personal will to power as ferocious as any Caesar or Bismarck, and his quest for dominance on the sporting field was sharpened by a sense of vengeance for past injustices off it. He punished the English for colonising West Indies and Australia for humiliating their cricketers in the summer of 1975-76.

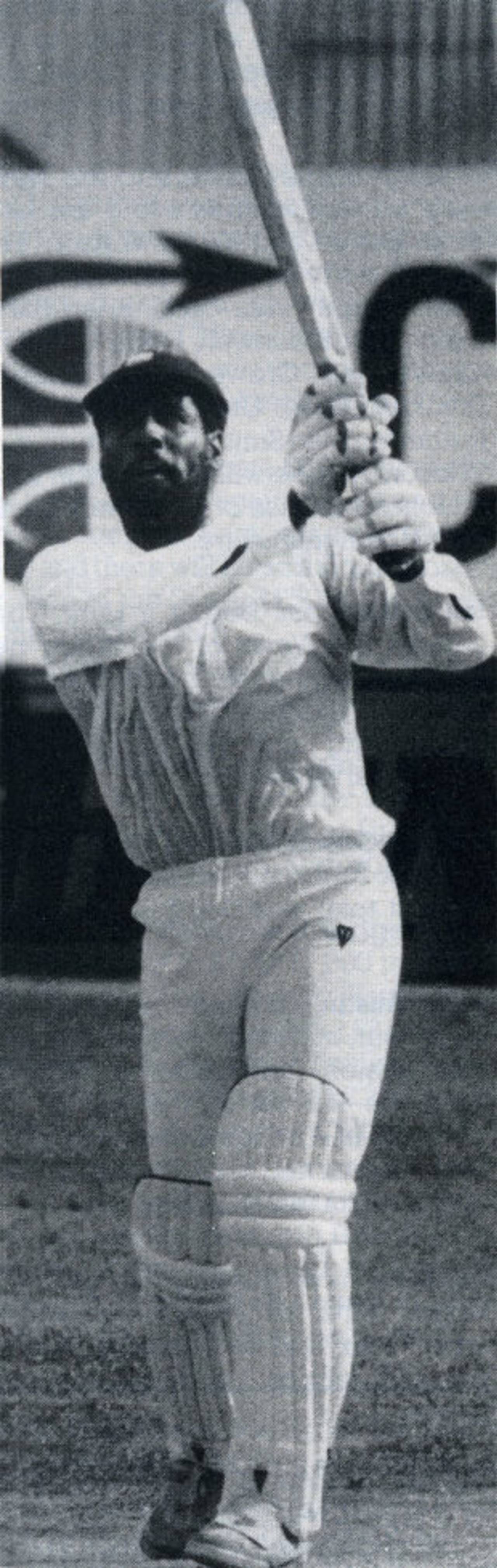

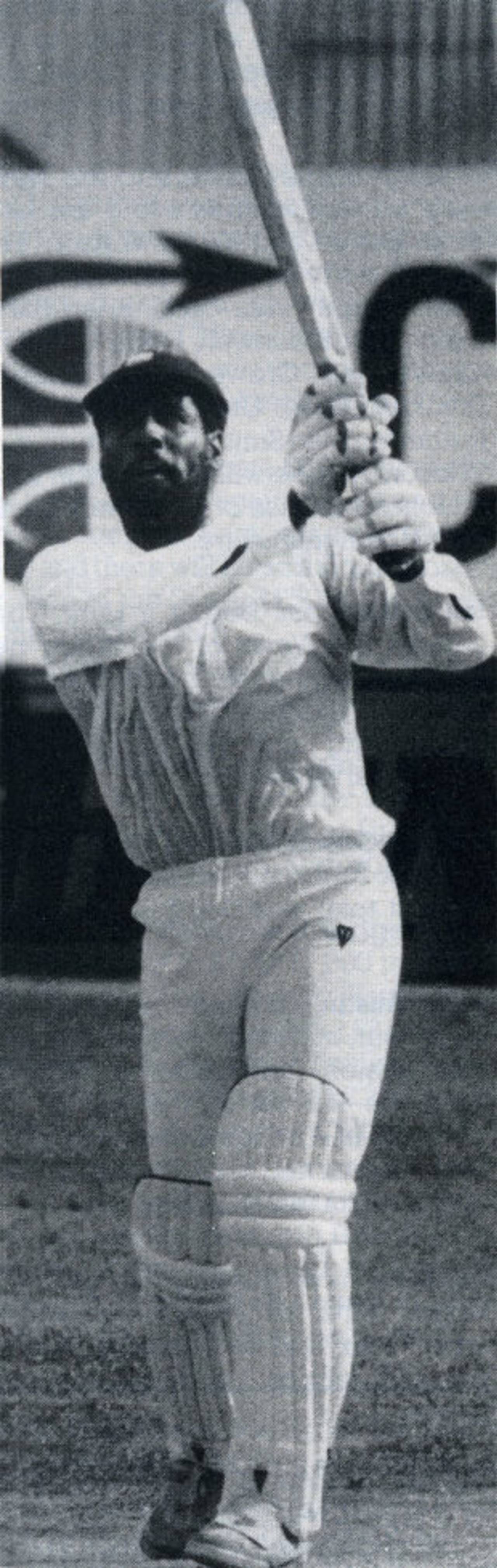

In an era stalked by the fastest and most dangerous bowlers in history, Richards never wore a helmet. Not once. Not against Lillee and Thomson. Not against Khan or Kapil Dev or Garth le Roux. Not even against his own team-mates: Holding, Roberts, Garner, Marshall and the rest of the Caribbean express. As his batting contemporaries wrapped themselves in increasingly sophisticated layers of armour, Richards trusted his life to his eyesight and his nerves.

He was called the Black Bradman, not so much for his capacity to amass enormous scores but for his inhuman ability to see a ball almost before it had been bowled. Such were his reflexes that the fastest of bowlers were frightened of him. He monstered them, physically abusing them, terrifying some and destroying the confidence of others, shortening their careers by the savagery of his assaults on their bowling. Whether in creams or coloured uniform, Richards lived and died by one credo: it was either he or they.

He arrived at that mantra on his first tour to Australia in 1975-76, with Ian Chappell's team in full flight behind the berserkers of Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson. So fast were they bowling at that point in their careers that they were quite literally unplayable. Thomson, in particular, could send a ball screaming from one end of the pitch to another in less time than science tells us a human being can possibly react.

And Richards played that series as the West Indians would play every series for the following decade or so. That is, at full tilt - with maximum prejudice and malice directed at the fast men who were trying to undo him. No matter how short the ball, or how steeply it rose off the pitch to tear at his throat, he fairly skipped on to the front foot to smash away one boundary after another.

He had Chappell's ability to humiliate a bowler. But he brought with him to the pitch a much darker sense of coiled menace and evil intent. He played with perfect timers of the ball like Sunil Gavaskar and Zaheer Abbas. He played with thuggish enforcers like Ian Botham. But none of them came within a shadow of combining Richards' rare sense of timing, his frighteningly muscular physique and his heavyweight's ability to hammer down an opponent. For all their blinding pace, both Lillee and Thomson spent much of that summer standing helplessly, mouths agape, as their lightning bolts screamed back overhead to clatter loudly into sightscreens and picket fences. Richards - half-smile,

half-sneer - dared them to bowl faster.

He was supposedly a nervous starter, although he masked any lack of confidence with that brutish swagger and general air of lordly disdain. He would dispense with any anxieties through the simple process of smashing the opposition to a pulp before they could dare exploit a perceived weakness. It made him a fiendishly difficult problem for opposing captains, who could see two days of ascendancy demolished in half an hour. And all this, of course, made him especially devastating in the shortened game, when there was no time to recover from a plan gone badly awry, where the fast bowlers who were his natural enemies were hobbled by fielding restrictions and the limited number of overs they could deliver.

Kapil Dev remembers two shots in the 1983 World Cup final when Richards carted balls from way outside off, smashing them around to square leg. "My line was on and outside the off stump, to get him out with my outswinger. On both occasions I threw my arms up expecting an edge, only to see the umpire waving his arm to signal a boundary."

Imran, who thought Richards the greatest batsman of his generation, recalls the Master Blaster handing out similar treatment to his Australian nemesis in a World Series Cup match. "He advanced down the wicket at Thomson, at his fastest and armed with a new ball. He smashed a short ball from him to the mid-on fence."

When Richards played one of the greatest innings in cricket history it was not in a Test but a one-dayer - and it was against his most cherished victims, the Poms. His 189 not out at Old Trafford in 1984, from only 170 balls and out of a team total of 272, is rated by Wisden as the greatest one-day knock of all time.

For Richards, demoralising hapless Englishmen was something of a raison d'être. They had foolishly baited him before their first encounter, England's captain Tony Greig vowing that he and his motley crew of semi-geriatric plodders would make the Windies "grovel". It would have been an ill-advised comment at the best of times. Coming from a South African mercenary in some of the darkest days of the apartheid period, it galvanised the feelings of Clive Lloyd's young West Indians. On hearing of the insult, Richards famously spoke of himself in the third person.

"Nobody talks to Viv Richards like that."

For a young man he had a well-developed sense of his own greatness. At 16 he'd earned a two-year ban for dissent when he refused to leave the wicket on being dismissed for a duck. A riot ensued and the crowd could be calmed only by his recall. He scored another duck. And made it three goose eggs when he failed to trouble the scorers in the second dig. His curious record of three ducks in one match is a piece of cricketing arcana but goes to demonstrate that, even as a stripling, he would not suffer the insults of lesser beings without consequence.

As he matured Richards learned to exact his vengeance with the willow. In 1976 he took 829 runs off Greig's side in only four Tests. A few years later, in 1979-80, he destroyed the career of Australia's Rodney Hogg after the slab-shouldered paceman was foolish enough to smack Richards a painful blow in the head with a bouncer on the unreliable MCG deck. Chewing gum like a waterfront contract killer, the champion No.3 gave Hogg the stone face before dismembering his next six overs. Hogg ended up going for 10 an over and had to retire from the field with a strained back. It was another year before Hogg stepped on to a Test match field, and never again did he regain the penetration of his earliest days when he routinely embarrassed Geoff Boycott.

There was a curious price to be paid for all this inhuman brilliance. Those West Indian sides were overburdened with talent, but so dominant was Richards that if he stumbled it was possible to bring the whole team down around him. In 1983 they lost a World Cup final to India simply because Richards couldn't contain his natural flamboyance and threw his wicket away at an inopportune moment.

Australian cricket remembers him with bittersweet fondness as the man who kept a studded boot on their throat throughout the 1980s. Shane Warne was just a fat kid from the burbs back then. The national side was first riven by conflict between loyalist players and the original World Series defectors, then gutted by the defection of more than a dozen players to a rebel series in South Africa. It was one of the darker periods in local sporting history. Richards was responsible for ensuring it didn't get any better so long as he had a say.

Only Lillee had any answers. Lillee never made Richards his bunny, but no other bowler in the world had as good a chance of removing the dynamo. It is telling, however, that Lillee rarely - if ever - beat him for pace. He generally bamboozled Richards on to the back foot and trapped him leg-before with cut and swing, not brute speed.

If Australia were ever to prove competitive against their tormentors through that era, it meant getting rid of Richards early. It was more often a dream than reality.

John Birmingham is the author of He Died With A Felafel In His Hand and Leviathan. His latest book is Dopeland.