|

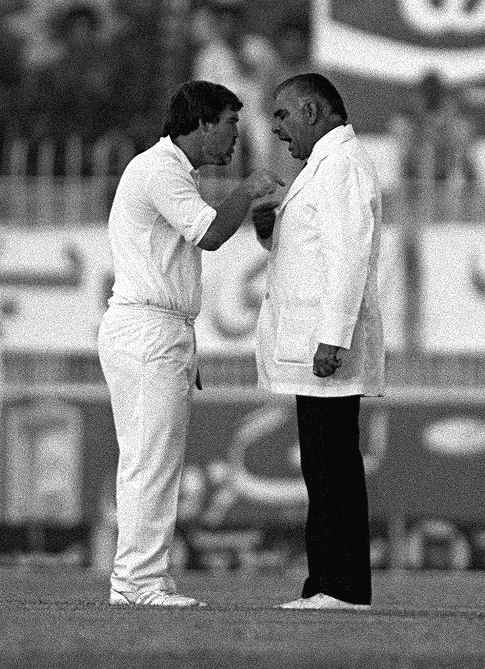

Shahid Afridi's pitch-dance at Faisalabad was yet another colourful chapter in an eventful rivalry

© Getty Images

|

|

It is in cricket a rivalry unique. It does not rely on the conventional ingredients that form the undercurrent of most traditional rivalries: geography, religion, a tainted historical antecedent. Yet it has been as fractious, as heated, as packed with history, incident, drama, plots and sub-plots as any. Contests between Pakistan and England, by rule, have not been dramatic; often they have been direly one-sided, often deathly dull. Yet, always they have been loaded. It isn't, as with India and Pakistan, a matter simply of love or hate, moulded by prevalent political winds. It isn't, as with the Ashes, tied inexorably to a history that has shaped the game itself.

Although there is considerable emotion, some history, and even a colonial legacy, there is a whole lot else that is more compelling. And precisely because the strength of antagonism is dictated by unconventional sources, it is maddeningly complex.

Barring a handful of contests - the 1954, 1971 and 1996 tours to England by Pakistan - nearly every series, irrespective of venue or decade, holds something: controversy, theatre, intrigue. Even the mostly friendly 2005-06 tour of Pakistan produced at Faisalabad two controversial dismissals, a blast during play, and a ban for Shahid Afridi for scuffing the pitch. Each series has added a layer of subtext, some acrimony, some implication, some "previous" onto the next. As a relationship, progressively through the decades this one has mostly worsened, interrupted only sparingly by clashes which have merely left the status quo unmoved.

In 1955, when Donald Carr's MCC toured Pakistan, a template of umpiring mistrust and discontent was set. The tourists complained about umpire Idrees Beg, then infamously doused him with cold water in Peshawar - allegedly as a prank. The series would have been abandoned but for diplomatic intervention; the tourists claimed Beg came voluntarily. Beg and other Pakistani officials asserted he had been kidnapped.

Ted Dexter's tourists in 1961, on what was an amicable enough tour, came across, according to reports, "reasonable umpiring, although criticism came here and there". The sending back of Haseeb Ahsan from England in 1962, at his captain's behest after Haseeb's action was whispered to be less than legitimate, unfurled its significance two decades later when he toured as manager in 1987. That tour, of course, was steeped in confrontation and Haseeb was widely condemned by England as the instigator.

In 1967 and 1974, Pakistan rumbled about inadequate covers allowing water to seep through at the English grounds. Even in between, in the Pakistan of 1969 and 1973, in encounters relatively free of rancour, there was the embellishment provided by political turmoil. The first of those series was played against the backdrop of Bangladesh's impending birth and abandoned after riots in the third Test at Karachi; Wisden called the tour a fiasco. The second went ahead after extra security was arranged for the tourists. The British mission in Islamabad had received a hand-written threat from a group called Black September promising to harm the team.

From there on, the rivalry has spiralled: through the late seventies travails of the Packerites and the felling of Iqbal Qasim by Bob Willis at Edgbaston. It reached its confrontational peak, of course, in the spectacularly raucous mid-to-late-eighties and early-nineties contests, when familiarity bred hatred (the sides played 11 ODIs and eight Tests between December 1986 and December 1987, in those days considered overkill).

What makes it what it is? Pakistan and England ostensibly provide cricket's affirmation of Samuel Huntington's thesis of the clash of civilisations. Huntington's treatise of the same name, which examines potential ideological and cultural conflict post-Communism, serves to explain, superficially at least, the incendiary nature of this rivalry.

Javed Miandad, no two-bit extra in these dramas, sagely substantiates this in his autobiography: "Underlying cultural differences are always a fertile ground for misunderstandings." Certainly, as Simon Barnes argued before England's 2000 tour to Pakistan, two more culturally divergent sides on the field are difficult to find.

Barnes wrote, "The fact is that Pakistanis are not only different to the English, but they really don't mind. They don't see their culture clash with the English as a personal and national failing; they suspect that there might be problems on the English side as well. Like arrogance and xenophobia and Islamophobia, just for starters."

|

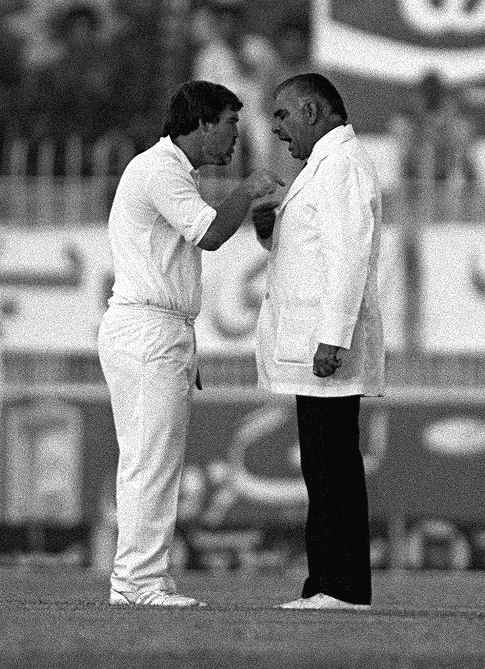

Mike Gatting and Shakoor Rana face off

© Getty Images

|

|

The behaviour of administrators further augments this line of thinking. The planning and method which seems to infuse every action of the British is anathema to Pakistan, where only the last minute is the most important - as was learned by, for example, the English tourists of 1968-69, who were disgruntled more than once by the inconvenience of last-minute venue changes.

Both sets of players collectively and individually are, inevitably, subjects of caricature-ish, sometimes rude, profiles in the other's backyard; if Pakistan is the abrasive, deviant child, inclined to deception and erratic behaviour, then England is the uptight, grumpy old man, moaning about anything and everything, bringing his own food, and unwilling to mingle.

Pakistan's heroes are portrayed as geniuses - sometimes mystical as in the case of Abdul Qadir, and sometimes warrior-like, as in that of Imran Khan and Wasim Akram. Imran, aware of this flimsy characterisation, prompted Qadir to grow his hair and a goatee to further heighten his numinous aura. Pakistan's villains have been devious, conspiratorial and antagonistic, as Javed and Haseeb were deemed.

Simon Heffer's remarkably distasteful piece for The Sunday Telegraph in 1992 - "Pakistan - The Pariahs of Cricket" is the best example. Miandad was likened to a rickshaw driver and card-sharp; Pakistan was labelled a country of cheats, capable of fair play only when their grounds were "turned over to their other popular use, as stadia for public flogging."

England's heroes have been plodding, but with innate goodness and uprightness of spirit - a Colin Cowdrey or a David Gower. Their villains have been pantomime - racist, colonialist and obnoxious like Mike Gatting and, of course, Ian Botham. The latter is remembered not so much for his 8 for 34 in 1978 as for his mother-in-law. Nothing has existed in between, and it is a seductive contrast.

Add to this superficially enhanced clash considerable colonial residue and you have the beginnings of a dysfunctional relationship. Imran and Javed argue that the atmosphere only soured once Pakistan began asserting itself as a powerful Test nation in the late seventies and early eighties. As the one-time subservient colonised - tolerated for one-off successes like the Oval in 1954 - challenged at the very top, asserting a regular authority over the supercilious coloniser, the clashes became increasingly fraught and disputatious. A fundamental relationship was overturned.

In a Daily Telegraph column about his retirement, Imran writes about how breaking free from mental "colonial shackles" and ridding Pakistan of its inferiority complex - where the ultimate ambition of every manager of a tour to England was to be elected to the MCC - was one of his most cherished achievements. Javed, naturally, was blunter. "For years, Pakistani teams on foreign tours found it difficult to shake a sense of inferiority. Perhaps we were embarrassed to be from a Third World country that not too long ago had been ruled by white colonialists."

Although, like with the cultural clash, there is undeniable truth in this argument, it too lacks depth. Revenge, colonial-style, was certainly on Aamer Sohail's mind when he directed Botham to send his mother-in-law to bat next after a cheap dismissal in the 1992 World Cup final. But it overlooks, one, a quintessentially Pakistani paradox and two, a legitimately questionable English outlook, that have together added, if it was needed, a little extra zing. Now it gets complex.

In broad swathes of Pakistan there is a deep-rooted contradiction towards the English (and Western civilisation). For a pot pourri of reasons - colonial, religious and cultural - they generate animosity. Post 9/11, this has intensified. Yet in this same country it is a widely held and cherished ambition to move westward and seek opportunity, fortune, and a better life.

Similar paradoxes exist in cricket. One disconnect is exemplified best by Imran's own experience of, and attitude towards, England, as Ivo Tennant hints in his biography. Imran was seen by many in both countries as a product of English society. He had studied there but more importantly had attuned himself socially; he was accepted. Yet publicly he spared no chance to express his distaste for "parochial English attitudes".

Imran writes about how breaking free from mental "colonial shackles" and ridding Pakistan of its inferiority complex - where the ultimate ambition of every manager of a tour to England was to be elected to the MCC - was one of his most cherished achievements

Imran writes about how breaking free from mental "colonial shackles" and ridding Pakistan of its inferiority complex - where the ultimate ambition of every manager of a tour to England was to be elected to the MCC - was one of his most cherished achievements

|

Given his background, the contests of 1982 and 1987, over which he presided, should not have been as thorny as they were. In the event, Imran at least managed to emerge unscathed, being careful enough in 1987, as Tennant outlines, to ensure that Haseeb did his bidding on contentious issues such as umpiring. Haseeb was demonised, Imran tolerated. Javed rationalises this with a thinly veiled dig at Imran: "Those who try to conform are better tolerated... if I too had gone partridge shooting... or had been photographed in morning dress at the Ascot, people would have found me more palatable."

The other inconsistency is related but afflicts the Pakistani cricketer in general. For all the alleged resentment he bears, and the perceived injustices he has suffered at the hands of the English, he has traditionally held performing well in England in great regard as a benchmark of achievement. Performances against England in England guarantee folklore, acclaim; Zaheer Abbas's double-hundreds, Fazal Mahmood's 12, Asif Iqbal's 146, Mohsin Khan's and Javed's doubles. Javed, who skippered the cantankerous 1992 tour and was persistently demonised there, is reverential. "There is something special about playing in England, because you really have to do well against England, in England, to get the stamp of accomplishment in world cricket," he writes. He's not alone; Pakistani autobiographies are rare, and rarer still are those without a chapter on England and the English. Akram gives them five chapters.

Further, for many Pakistani cricketers, county and league cricket have long been considered the ultimate education. Imran praised, exultantly, the county system, saying, "there is no better school in which to learn how to play cricket and to polish one's talent". In the last three decades, many Pakistanis have spent summers in England, improving both their game and socio-economic status.

Shouldn't familiarity with the players, the country, its norms and traditions, make for less fractious encounters at the international level? But barring 1996, when Lancashire team-mates Akram and Michael Atherton ensured a refreshingly cordial series, and 1973, when Majid Khan and Tony Lewis, ex-Cambridge and Glamorgan mates, skippered a dull but friendly one, the majority of encounters in which Pakistan had a sizeable contingent with strong county ties have been riddled with misunderstanding and suspicion.

Undoubtedly these inconsistencies at the heart of the Pakistani approach to England have contributed to the nature of the relationship.

Almost as much, perhaps, as a beguiling yet genuine duplicity in England's approach to the relationship. Take umpiring for instance, which forms, outwardly, the basis for so much. When a former England player remarked after Faisalabad 1987 that Pakistani umpires had been cheating England for 35 years, it was a comment born of a systemic, rigid belief - unwavering as any in religion - that Pakistani umpires were biased. As Martin Johnson explained in Wisden of Faisalabad, "At best, they had come to regard the home umpires as incompetent; at worst, cheats."

Even Scyld Berry, in Cricket Odyssey, a diary chronicling the tumult of that tour, portrays the appointment of Shakeel Khan, and later Shakoor Rana, as part of a byzantine conspiracy designed solely to cartwheel the English, deliver victory, and assuage a nation baying for blood. Rare has been the Pakistan tour to not contain some reference, snide, muttered or public, about the umpiring.

Two points must be raised here. One is generic; in the days before extensive, super slo-mo TV replays, how much conviction could be invested in the belief that a decision wasn't just wrong but deliberately so? Even today, with all the technology available for lbws, thin edges and line calls, definitive judgments remain dicey. How credibly can we treat the belief that a majority of past decisions have been incorrect on purpose?

|

Chris Broad wasn't a happy chappie on that ill-fated tour in the late '80s

© Getty Images

|

|

The other, more pertinent point is this: much indignation was expressed in 1987-88 when the Pakistan board refused to accede to the tourists' request to remove Shakeel Khan from the umpire panel. They felt he was incompetent and biased. Yet when Pakistan as tourists had made a similar request to the England board asking for David Constant to be replaced not six months earlier, their request was declined and leaked to the press as evidence of their gall. In contrast, India's request five years earlier to have Constant removed had been accepted.

Constant had officiated at Lord's in 1974 and had decided Pakistan had to play on a pitch on which inadequate covers had allowed water to seep through. Derek Underwood took eight wickets, and although the match was drawn, the Pakistani management lodged a bitter complaint with the English cricket board.

At Headingley in 1982, Constant contentiously adjudged Sikander Bakht out, potentially costing Pakistan the match and the series - a decision that has riled Pakistan more than any other. In Cricket Odyssey, Berry admits that appointing Constant was instigatory but cannot quite bring himself to believe Constant would ever cheat. Constant may be "abrasive" in his officiating, but Berry is convinced it is the manner of his decisions rather than the decisions themselves which so enraged Pakistan.

Could the same be said of the brothers Palmer, Ken and Roy? After the latter was involved in the Old Trafford fracas with Aaqib Javed in 1992, elder brother Ken (never a favourite of Pakistan's, and accused by Khalid Mahmood, Pakistan's manager in 1992, of ball-tampering during his playing days), adjudged Graham Gooch not out when he was run out by at least three yards in the next Test, at Headingley. Pakistan appealed themselves hoarse during that Test and not much of it, noted most newspapers, was frivolous. Irrespective of evidence, England's suspicions of Shakeel were similar to Pakistan's of Constant or Palmer, and yet, we're given to believe, they were somehow not.

In fact, appealing itself sheds light on England's attitude. For years, Pakistan have been derided for their appeals on the field. Politely, their excessiveness has been "energetic", but it has also been a source of friction and resentment. Bob Willis, England's captain in 1982, chastised Pakistan for their incessant appealing, proclaiming it "was histrionic and Imran should have controlled it. Pakistani cricketers adopt the attitude of press-ganging the rest of the world in what they want."

Willis's ire stemmed from thinking of it as an affront to the umpire and to the spirit of the game. Yet two of the most dramatically insolent acts, by far, against officials on the field have been perpetrated by two Englishmen, on the infamous 1987-88 tour. The circumstances were extenuating in Chris Broad's refusal to walk for a whole minute after he was given out at Lahore, but he was neither the first nor the last of his species to have felt hard done by at the hands of an umpire. Why he snapped then and there we don't know, for he had received poor decisions against Pakistan - from Australian and English umpires - through the year and had protested only meagrely then.

Faisalabad, as Simon Barnes argues, revealed nothing more than an absolute refusal by an Englishman to bow to a Pakistani authority. The English cricket board punished each player of that touring party with a "hardship bonus", thereby officially endorsing the view that Pakistani umpires, at least, could be affronted with abandon

Faisalabad, as Simon Barnes argues, revealed nothing more than an absolute refusal by an Englishman to bow to a Pakistani authority. The English cricket board punished each player of that touring party with a "hardship bonus", thereby officially endorsing the view that Pakistani umpires, at least, could be affronted with abandon

|

And how many captains have, like Mike Gatting, vigorously indulged in a finger-pointing slanging match with an umpire? Faisalabad, as Simon Barnes argues, revealed nothing more than an absolute refusal by an Englishman to bow to a Pakistani authority. The English cricket board punished each player of that touring party with a "hardship bonus", thereby officially endorsing the view that Pakistani umpires, at least, could be affronted with abandon.

Neither is this duplicity time-bound nor restricted to umpiring. Lord MacLaurin, then chairman of the England cricket board, suggested before the 2000-01 tour, significantly the first by England for 13 years since Faisalabad, that Pakistani players implicated (not proven guilty, mind) in Justice Qayyum's report on match-fixing should be suspended from playing. When Alec Stewart was named during the same series for alleged involvement, was Pakistani resentment at his continued participation through the series not understandable?

What, too, to make of reverse swing? Righteously condemned as an illegal concoction of bottle-tops and fingernails in 1992 when Wasim and Waqar were rampant, it is now an art form to be marvelled at. In 13 years, like an ex-con it has undergone a complete and successful rehabilitation. On the back of reclaiming the Ashes, it has become legit.

Given this overbearing context, the rivalry cannot be anything but unique. And, as Kamran Abbasi has pointed out in recent years, with the continuing evolution of the expatriate cricket fan, clashes aren't likely to get any simpler.

There was a time in the sixties when Pakistani-origin fans were mildly exuberant, never disruptive. Occasionally they would foray into the rowdy, as when mobbing Asif Iqbal at the Oval in 1967 when he reached that hundred. Even in 1987, when racial trouble flared at the Edgbaston one-dayer, clouding over a breathtaking contest, the incident was a relatively isolated one. But over the decades, as a second generation of Asian Briton has matured, Abbasi found that "a new Asian cricket fan had emerged, one passionate in support of a faraway land".

In 1992, a pig's head had notoriously been thrown into a Headingley stand full of Asian supporters. By the NatWest Series of 2001, against (and perhaps fuelled by) a backdrop of racial violence and, in Abbasi's words, "provocative National Front and British National Party posturing", overt enthusiasm had given way to perturbing acts of defiance. The media, predictably, heightened the tension by stereotyping the fans as thugs.

A link between the difficulty the Pakistani-Briton, as opposed to his Indian counterpart, has faced in integrating effectively into Britain, and the growing volatility of the fans can be argued, especially if you consider that one of the bombers involved in the July 7th bombings in 2005 was of Pakistani origin and loved cricket. But certainly the second generation has volubly expressed its alienation and sense of dislocation in British society, more so than their predecessors.

In any case, the support prompted Nasser Hussain to balk at the number of young Asians supporting Pakistan during the 2001 series; it prompted Old Trafford, home to a large Pakistani community, to market the Test as a virtual home game. And this was, remember, before 9/11 and 7/7, two events so cataclysmic for the Pakistani immigrant that it is impossible to predict how their impact will play on relations in the long term. Suffice to say, during Pakistan's current tour of England, the various fundamental equations governing the relationship between the two are likely to enter a different and possibly more volatile realm altogether.