|

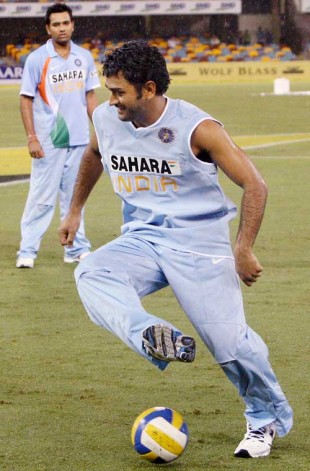

Kicks for free: MS Dhoni stands to earn about $90,000 per match in a form of the game that is far from the premier version

© Getty Images

|

|

In his early twenties, when many referred to George Best as the fifth Beatle, the world was his oyster. With his bright eyes, flowing locks, designer shirts, a Jaguar E-type in the garage, and skills that have seldom been seen on English football pitches since, Best epitomised the hedonistic 60s and a break with the bleak austerity of the post-war years. In those days he was on about US$295 a week - more than what Bobby Moore, England's World Cup-winning captain, earned.

According to an article in the London Times last November, inflation over the last 40 years stood at 1257 percent. Going by that figure, you might have expected today's top English Premier League footballers to be earning in the region of $3500, still significantly more than your average office worker. Think again. The average pro takes home $41,000 a week, after factoring in win bonuses and other performance-related incentives.

The big boys, though, are on a different plane. Chelsea's John Terry negotiated a new contract last year which made him the richest player in the league's history, with a weekly wage of $264,000. Eight others made over $196,000, while the likes of Fernando Torres at Liverpool and Didier Drogba at Chelsea had to make do with a mere $176,000. The numbers are similar for the top stars on the continent, such as Ronaldinho and Kaka. It's a measure of how far football has come in the new commercial age that no one needs to look enviously across the pond at US sports.

Tom Brady, who recently came very close to taking American Football's New England Patriots through a perfect season, signed a six-year deal worth $60 million in May 2005. His greatest rival, Peyton Manning of the Indianapolis Colts, earns more, but the seven-year contract worth $99.2 million Manning inked in March 2004 only puts him in the same ballpark as Terry.

On Wednesday, cricket entered that salary stratosphere, with the sort of rewards that former Indian cricketers who earned little over $6 for a Test match back in the 60s wouldn't have dared dream of. The Chennai franchise's bid for Mahendra Singh Dhoni didn't just surprise the other seven teams, it also blew the lid off the cricket economy.

Even today, a Test match appearance fetches an Indian player just over $5900, and the Indian Premier League's player auction may just have some reassessing the worth of their international careers. Adam Gilchrist has already bid adieu to international cricket, and Shane Bond has seen his contract with New Zealand torn up so he can play for the Indian Cricket League, the rival competition that's treated like a leper by the establishment. Even Darren Lehmann, who retired recently, is talking of a comeback so he can take a healthy nest egg with him into the Adelaide sunset.

The only difference between the cricketers and these others is, the latter really have to earn the big bucks. The American Football season lasts just over 20 weeks (if you make it to the Superbowl), and the likes of Brady and Manning are targeted for the worst treatment by behemoths on the opposing defense. The same goes for footballers like Liverpool's Steven Gerrard, who runs up to 13km during the course of a game. If you factor in England internationals and friendly games, Gerrard plays more than 60 matches in a season that lasts ten months. In the process, he would likely have inspired the defeat of a dominant Internazionale of Milan, and pitted his skills against Aresenal and Manchester United in games of the greatest possible intensity.

| |

|

|

|

| |

| All Dhoni has to do is play 16 games for cricket's version of the Harlem Globetrotters. Not even its most passionate backer will say that Twenty20 is the ultimate test of a cricketer's skill. That remains Test cricket |

| |

For six weeks of IPL work, Dhoni will bank $1.5 million, marginally more than Gerrard makes in the same period. All Dhoni has to do is play 16 games for cricket's version of the Harlem Globetrotters. Not even its most passionate backer will say that Twenty20 is the ultimate test of a cricketer's skill, the game's answer to a Milan derby or the Patriots v the Colts. That remains Test cricket. Outwitting Australia at the WACA or defying India on a turning track in Delhi - these remain the game's most arduous assignments. Miscuing a six over midwicket on designer flatbeds in a hit-and-miss format doesn't even compare.

The IPL's stated aim is to encourage people to take up sport, and promote young cricketers. Presumably, they also want to attract the sort of fanatical support that acts as an invisible 12th man for teams like Liverpool. But with many players not attached to their local franchises, it's hard to see how that will happen. Why on earth is Manoj Tiwary playing for Delhi, Rohit Sharma for Hyderabad and Robin Uthappa for Mumbai? In football, players choose their clubs. Torres turned down many to come to Liverpool, while Kaka stays on at Milan despite everyone else drooling over his talent. That makes it easier for fans to embrace non-local players, safe in the knowledge that the new icon isn't just some mercenary out to make a quick buck.

The sort of money thrown at young players in the IPL - is Tiwary really worth twice as much as Michael Hussey, even if Hussey only plays half the season? - should also make us wary.

American Football offers the greatest cautionary tale of too much, too soon. A few years ago, Michael Vick of the Atlanta Falcons was the most exciting quarterbacking talent around, the future of the league, and in possession of a contract worth $130 million over 10 years. These days he languishes in a penitentiary in Kansas, after a federal investigation exposed his involvement with Bad Newz Kennels, a pit-bull fighting and gambling syndicate. No one should expect young sportsmen to be role models, but you also don't want them to end up like Vick, or Best, who died an alcoholic a couple of years ago.

Perhaps the last word should go to Stephen Jay Gould, one

of the great scientists of our age, who fell in love with sport in an era

where excess wasn't the common denominator. "No one can reach personal

perfection in a complex world filled with distraction," he wrote about his

great idol, Joe DiMaggio. "He played every aspect of baseball with a fluid

beauty in minimal motion, a spare elegance that made even his rare

swinging strikeouts look beautiful ... a fierce pride that led him to retire

the moment his skills began to erode."

Hopefully, we'll be able to say that one day about some of those who have

clambered aboard the IPL gravy train.

Dileep Premachandran is an associate editor at Cricinfo