Show me a person who gave Kapil Dev's team any chance of winning the 1983

World Cup: I will show you a liar and an opportunist.

The story of how David Frith, then editor of Wisden Cricket Monthly, had

to literally eat his words after he wrote India off as no-hopers has been told far too often to be repeated here, yet is symbolic of the utter disdain with which the Indian cricket team was viewed before the tournament. To paraphrase Winston Churchill, the situation was "hopeless, but not serious."

My own belief in the Indian team's prospects, too, tended towards zero. True, there had been some glimpses of excellence when Kapil Dev's team beat mighty West Indies at Berbice in a one day game preceding the 1983 tournament, but India's track record in one-day cricket, and especially in the two previous World Cups, had been pathetic to say the least.

So while I was obviously privileged to be covering a World Cup, on the nine-hour flight to England in May 1983, two issues jostled for pole position in my mind: Did I really want give up law practice to pursue writing on cricket as a vocation? And secondly, did it make any sense to watch India play West Indies at Old Trafford first up when I could watch England play New Zealand at the Oval?

By the time the plane landed at Heathrow, at least one issue had been resolved. The Oval it would be. This decision was not, as might be misconstrued, based on the kind of cynicism journalists are known to acquire over a period of time. I was on only my second overseas assignment, un-jaded and curious, but frankly, what logic in watching India play the best team in the world?

I have lived to regret that decision. Watching the classy, elegant Martin Crowe was a delightful experience in itself, but not seeing India floor the mighty West Indies was such a bad miss that I was immediately chastened.

The topsy-turvy nature of sport is something only the foolhardy would ignore. This lesson had been painfully learnt. For the next month and more, I followed the Indian team diligently across the length and breadth of the country, spending long hours on British Rail, making scores of trips on the London Underground, as the World Cup wound its way through that magnificent summer. The budget was modest, the travel itinerary intense but the experience was unbeatable - and there other attractions an English summer offers, like catching a concert by Dire Straits at Earl's Court.

Thatcherism was taking firm control of political and economic life in England in the early 80s, and Prime Minister and "Iron Lady" Margaret Thatcher was the undisputed Queen Bee. Only occasionally was she forced to share centre-stage with US president Ronald Reagan. In that sense, even the World Cup enjoyed miniscule importance, but for those weaned on cricket lore, England was still a dream come true.

The grounds of Sussex spoke of the exploits of Ranji, and the two Pataudis, apart, of course, from CB Fry. At Lord's, passing through the Grace Gates was like a pilgrimage in itself, though the good doctor himself was from Gloucestershire. But my personal favourite as a diehard Surrey fan was The Oval, home to Jack Hobbs, the Bedsers, and my childhood hero, Ken Barrington.

The World Cup carousel took me to most of these historic grounds. When no matches were scheduled, I made day trips to soak in the history and nostalgia. Through the tournament I stayed at Surbiton, a few stops from Wimbledon. My host was a young engineer I knew from Bombay, who was on a work permit and who knew everything about cricket, tennis - indeed all the sport played in England. "For a sports buff, there is no place like this," he would say. Oh, to be in England that summer!

There were only six journalists (if I remember correctly) from India. The explosion in the Indian media, with its din, clamour and suffocating competition to grab soundbites, was nearly two decades away. In 1983 there was still easy access to players and the dressing room.

I remember watching Dilip Vengsarkar get hit on the face by Malcolm Marshall from the dressing room. There was a flurry of abuse when the batsman returned retired hurt, and not from Vengsarkar, poor chap, who could barely open his mouth. When India played Zimbabwe in the historic match at Tunbridge Wells, I watched a fair bit of Kapil Dev's memorable innings, sitting next to Gundappa Viswanath, from just outside the dressing room. Vishy, who hadn't yet retired, had failed to regain his place after the disastrous tour of Pakistan, but was still an integral member of the Indian team.

He was also the main source of hope, I realised, as the team tottered. When India were 9 for 4, he was to say with a sense of righteous belief, "Don't worry, the match is not over yet." He must have been the only man then to believe this. Talk of prophetic words.

As the tournament progressed, the small media corps became almost like an extended family of the team, but this did not mean we did not look for "controversies". The composition of the team showed a distinct north-west divide so to speak, and anybody who knows anything of Indian cricket knows how much these things mattered in those days. Did it influence Kapil Dev? More importantly, was Sunil Gavaskar dropped for the first match against Australia, or "rested", as manager PR Man Singh insisted?

All such doubts died by the time Kapil Dev had finished his business at Tunbridge Wells. Gavaskar was back in the team, despite his mediocre form; Vengsarkar was still out of contention through injury; but by a process of trial and exigency India had hit on the right combination.

The academically inclined are still locked in endless debate about which has been the greatest ever one-day innings. In my mind there is no doubt that Kapil Dev's unbeaten 175 that day stands supreme. There have been bigger scores since, innings with more sixes and boundaries hit, runs scored at a faster rate, but for sheer magnitude of impact (in a myriad ways) nothing quite matches up to Kapil's innings. It not only helped India win victory from the jaws of defeat, but also dramatically altered the course of the tournament, and subsequently, the future of Indian and world cricket.

In the context of the tournament, this innings was to be a rallying cry from a field-marshal to his troops, as it were. Remember, Kapil was in his first season as captain, having taken over from Gavaskar after the rout against Pakistan a few months earlier. This change had been contentious.

Moreover, India had come into the World Cup on the back of a series defeat against the West Indies, and there were muted discussions on Kapil's future as leader even before the tournament began. The pressure on him was to not only justify his reputation as one of the game's greatest allrounders, but also to hold his team together, and thereby hold on to his captaincy.

Examine the scorebook and you find that India's performances till then had been modest -- despite the first-match win over the West Indies - and not at all indicative of the heady climax that was to follow. There had been a couple of exciting 50s, some of the swing bowlers like Roger Binny and Madan Lal were enjoying the helpful conditions, and the fielding was much improved by traditional Indian standards. But nothing to suggest that this was a world-beating side.

The next week flew past in a flurry of wins, banter and laughter as India knocked over Australia and England to earn a place in the final against the world champions. This was surreal stuff from a side which had now forged such enormous self-belief as to become unstoppable.

Australia were a team in disarray, with Greg Chappell not available, and unconfirmed reports suggesting massive infighting between some of the senior pros and skipper Kim Hughes. Having lost their first game, against Zimbabwe, the Aussies were on the back foot when they met India at Chelmsford. As it happened, neither Dennis Lillee nor Hughes played that game, and the result was a massive defeat which was to culminate in Hughes surrendering the captaincy in tears a year later.

The two semi-finals involved India and Pakistan. Could it be a dream final between the two arch rivals from the subcontinent? It was not to be, as Pakistan lost badly to West Indies. With Imran Khan unable to bowl, Pakistan relied heavily on their batting, but in this crucial match missed Javed Miandad who reported unwell. I happened to meet Miandad in his hotel room on the eve of the match. He was obviously suffering from influenza. I wondered, though, if he could miss such an important game; he did and that was that.

On the same day, India's players marched to Old Trafford like born-again gladiators, bristling for the kill. It was a surcharged atmosphere, and by the time the match ended in a flurry of boundaries by Sandeep Patil off the hapless Bob Willis, many fights had broken out between the fans of the two sides all over the ground. One placard captured the Indian performance and the result of the match tellingly: "Kapil Dev eats Ian Botham for breakfast".

So incredible had been India's run of success and such was the disbelief that even the stiff stewards who manned the Grace Gates were completely nonplussed. "Oh, we now have Gandhi coming to Lord's," said one to his colleague in an obvious reference to Sir Richard Attenborough's memorable film on the Mahatma when a few of us landed up to demand accreditation for the final. After some haggling, we were not to be denied accreditation for the match.

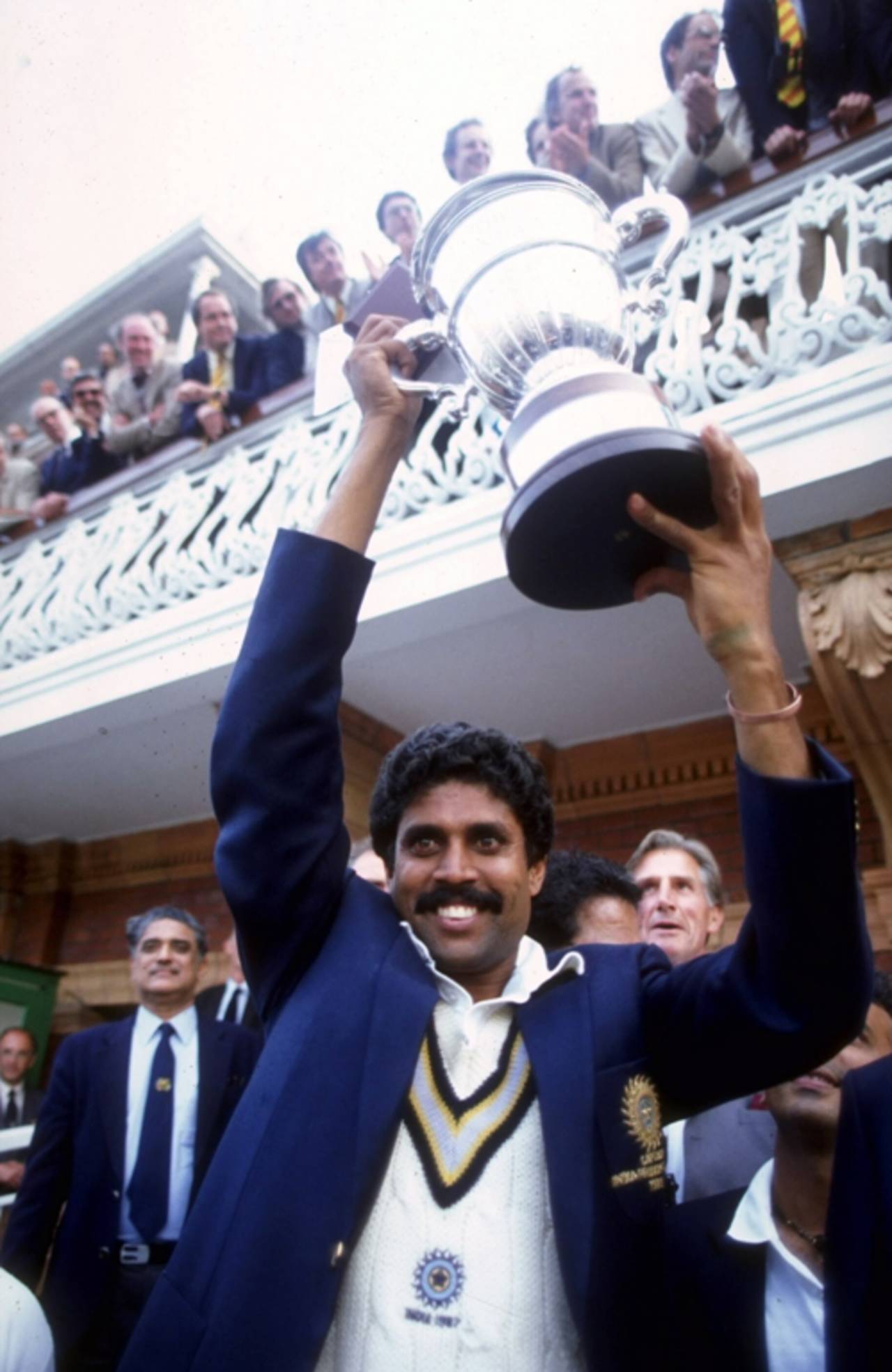

On June 25, India took the field against the West Indies, and within a seven-hour roller-coaster ride, the cricket world had been turned upside down, a billion lives changed forever.

At a personal level, the second issue which had dogged my flight into England had been resolved too: the law degree would find its place on the mantelpiece; writing on cricket was to be my lifeline.

Ayaz Memon is an editor at large at Daily News and Analysis. He has

written on cricket for more than 25 years