|

|

|

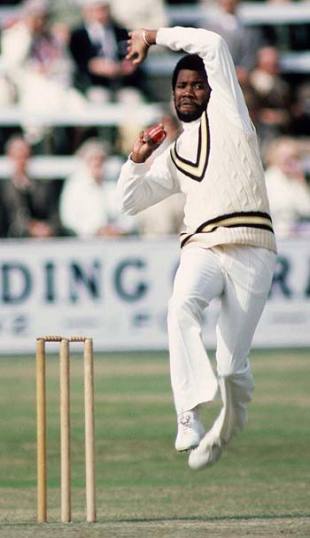

'By his own admission Marshall was a lazy youth, happy to hang out with his equally indolent pals on the beaches and in the Bridgetown parks'

© Getty Images

|

|

| |

At the tail-end of Grantley Adams Airport in Barbados, where Concorde once went to its mark to begin its own majestic run-up, lie the earthly remains of Malcolm Marshall.

In the tiny church of St Bartholomew, a black marble plinth, lovingly maintained, signals the final resting place of one of the great West Indian fast bowlers from an era when the Caribbean ruled the cricket world. A steady stream of cricket-loving

holidaymakers in their Mini Mokes have turned the grave into a shrine, all of them entranced by a moving poem written by his son Mali at the moment of his father's death and etched into the plinth.

On April 18, Malcolm Denzil Marshall would have been 50, should have been 50 but for the colon cancer undiagnosed for three years which crushed even his noble spirit half way through his 42nd year.

The worldwide outpouring of grief when Marshall, reduced to not much more than 25kg, died in November 1999 was testimony to the genuine love and admiration he engendered. Another great West Indian fast bowler, the Reverend Wes Hall, whispered the final prayers and ushered Marshall into the hereafter, as he believed he would be. In his last weeks Marshall had rediscovered his faith. The litany of cricketing mourners was a compelling tribute to his legacy. They had travelled across the globe to pay their respects and Barbados was an island plunged into gloom on the day he was laid to rest, silent crowds lining the streets to say their farewells as the cortège made its way to its final destination.

Not that Marshall ever spent long in Barbados once he began a 20-year career that took him abroad on a regular basis. In a way it was the constant travelling which contributed to his downfall, never being in one place long enough to get the body-twisting stomach pains properly treated. Too often he was told he had indigestion. At 50 he should have been at his coaching peak with plenty still to offer. Those of us lucky enough to know him prefer to remember the laughter and vivacity he spread in his wake like scattered stumps.

Marshall and I got on well, initially because we made each other money. I ghosted his book in 1986 and wrote his column in the Daily Mirror for eight years, rusty shorthand struggling to keep up with a mountain of words, machine-gunned

out in a Bajan accent he never lost. I was never sure I wrote what he said, but he never complained.

"Maco" liked brandy (not rum) and coke and he would deliver his sermons for me to scribble down as he knocked it back, his accent getting thicker and voice higher by the shot.

Sometimes I would need him urgently in places like Rawalpindi in the days before email and mobile phones. He would be on tour with West Indies and, for want of something to do, the players would drift in and out of each other's hotel rooms. I am fairly certain I did at least two Daily Mirror columns down crackling phones lines with players other than Marshall but they were happy to talk and it would have been rude to interrupt.

For a man as dedicated and in every sense the ultimate professional, it was a surprise to discover that, if it had not been for

the tenacity of an English businessman, Marshall's career would have been still-born.

By his own admission Marshall was a lazy youth, happy to hang out with his equally indolent pals on the beaches and in the

Bridgetown parks. Sir Ian Clark, managing director of Banks Brewery, wanted him for his club side but Marshall turned him down. Luckily for cricket, Clark persevered and won him round a year later by promising an undemanding day job. Within another year he was heading to India with West Indies, his first Hampshire contract in his back pocket.

Marshall went on to become statistically the most successful Test bowler of the 1980s, suppressing his desire to be recognised as a batting allrounder once it became clear his springy, skidding action could cut a swath through the best international batting. As far as I could make out, only three batsmen irritated him.

|

|

|

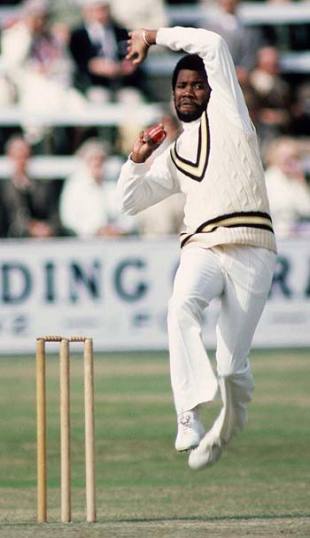

'Marshall went on to become statistically the most successful Test bowler of the 1980s, suppressing his desire to be recognised as a batting allrounder once it became clear his springy, skidding action could cut a swath through the best international batting'

© Getty Images

|

|

| |

In Dilip Vengsarkar's case it was more than irritation. It was an uncharacteristic blind hatred, at least in the early years. Vengsarkar had belittled him from slip at Bangalore in 1978-79 when the debutant Marshall was batting, constantly appealing until the umpire gave in under pressure and raised his finger for a dodgy leg-before. Marshall never forgave him and spent the rest of his career hunting down the great Indian batsman. No wicket gave him greater pleasure.

For no reason I could ever discover Marshall did not like Chris Broad, and the sight of Rehan Alikhan, the former Sussex and Surrey opener, maddened him. It may have been something to do with the batsman's perceived arrogance at the crease. In one county match Alikhan played and missed four times in succession. The silent assassin, who thought sledging had something to do with snow, finally lost his cool. "Somebody get him a bigger bat," he shouted in exasperation.

Marshall liked Geoff Boycott, admiring his technical correctness and his bravery. Whenever they played against each other, a curious ritual was enacted. As Boycott walked out to bat and Marshall prepared to bowl the first ball, Marshall would say: "You hookin' today, Boycs?" To which Boycott would reply: "Not today, Maco." Marshall would then bowl him a bouncer, Boycott would sway away from it, they would smile at each other and the match would begin.

On one surreal occasion I was a front-seat passenger in Marshall's car driving down from his house high in the hills over the west coast of Barbados when he spotted Boycott honing his batting with local youths willing to bowl to him on the rough-hewn pitch and then retrieve the ball from the undergrowth past grazing sheep. Maco slammed on the brakes, wound down the window and screeched: "Boycs, I'm coming to get you." Under his tan Boycott visibly paled. "No, no, I'm just finishing up," he said, putting the bat under his arm and vacating the crease at a brisk pace.

What he said, he meant, as he did at Pontypridd when playing for Hampshire. With two days remaining, Glamorgan were 13 runs ahead in their second innings with seven wickets left. Just before the start of play in front of a full dressing room Marshall rang his Southampton golf club and booked a tee-time for 4pm that day.

In the first session Marshall took six of the seven remaining wickets, leaving Hampshire 70 to win, which they accomplished before lunch. At 4.05pm Marshall was teeing off, apologising for being five minutes late.

It was a shame that Marshall's coaching career coincided with declines at Hampshire and West Indies, so that neither matched the success of his playing career. The sloppy attitude of the West Indian players particularly troubled him. For those of us who remember the one-armed bandit of Headingley 1984, the swagger of a man who knew his place in history, we would like to think Wes Hall was right when, from the funeral pulpit, he boomed: "Malcolm Denzil Marshall is safe and all is well with his soul."

This article was first published in the May 2008 issue of the Wisden Cricketer. Subscribe here