|

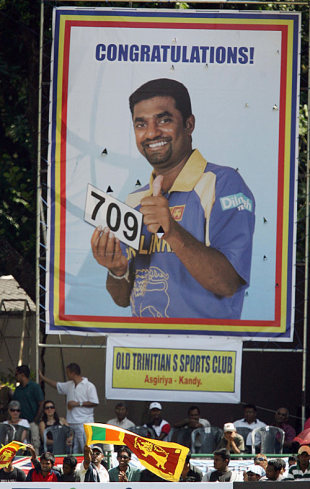

To Sri Lankans, Murali has gone beyond being merely a sporting hero; he is a national icon

© AFP

|

|

Spin bowling is often about masks and disguises, sleights of hand and tempting

arcs. Batsmen reach for the ball that is not there, or adopt a superior air, ignoring the one that seems set to go past but then inexplicably changes course. They are rendered illiterate - unable to read the spinning ball. Muttiah Muralitharan's greatness lies in the fact that even when batsmen read him, there is little they can do to keep him out. It is possible to say of him, as Albert Einstein did in another context, that generations to come will scarce believe that such a one as this walked upon this earth.

A good percentage of his victims were aware of what was happening, but helpless to

prevent the inevitable. "Aha!" you can imagine the batsman telling himself, "this

ball will spin so much, bounce this much; I know precisely where to meet it, with

my bat and pad close together." And then it spins just that bit more, bounces a

little higher, and Murali has his man.

For every spinner who tricks the batsman into seeing things that are not there and

believing things that will not happen, there is Muralitharan who shows him his

hand and kills him with the obvious. It calls for supreme self-confidence. There

is a palpable sense of fun too, as Muralitharan, the first wrist-spinning offspinner in

the history of the game, explores the physical limits of his craft. Clearly, there

can be only one Muralitharan. If there is to be another, we need to have the enormous good fortune of finding someone who is as flexible, as supple, as tough, as keen on

experimenting, as enthusiastic, as much in control. Impossible.

Let us, therefore, enjoy the art of this genius while we can. Muralitharan is 35,

and the demands on his body are huge. He has had surgery on his shoulder at least

twice; he cannot go on forever.

Few cricketers have had to shoulder his burdens - as a minority Tamil in a

strife-laden country, as a bowler worshipped and reviled in equal measure, as a

player in a team whose fortunes rose or fell according to his performance. In a

decade and a half at the top, he has won over everybody - both sides of the ethnic

divide and both sides of the bowling-action divide. His work after the tsunami

struck his country released him from the narrow confines of a sporting hero and

anointed him a national icon, all things to all people. Through it all he has

remained rooted, a charmer who finds it hard to believe that by merely doing what

he loves the most, he has rewritten the rules of his craft and extended the

limits of the possible.

The odd left-hander in the odd innings apart, no batsman has played Muralitharan

consistently with comfort. Yet, unlike most spinners, he didn't appear on the

international scene a finished product, every trick in place, every nuance worked

out, with only the minor detail of wicket-taking to follow. It took him 27 Tests to

claim 100 wickets; the hundreds thereafter came in 15, 16, 14, 15, 14 and 12 Tests

respectively. This wasn't a genius that was created behind closed doors, but one

that evolved out in the open, in front of thousands of spectators.

Every ball, every wicket, was tucked away in that remarkable mind; nothing was

forgotten, nothing was useless. Muralitharan is the man who remembers everything.

If he has got Rahul Dravid five times, it is because he remembers how the batsman has succumbed each time. The past is the pathway to the future. He has bowled nearly 40,000 deliveries in Tests - only Warne has bowled more - and remarkably, can recall most of them.

The turning point, according to Sanjay Manjrekar, came in Lucknow in 1994 after

Navjot Sidhu hit him for six sixes en route to a century. Muralitharan realised

that he was bowling the wrong length, shortened it slightly, and crossed the

bridge from the good to the great.

Every ball, every wicket was tucked away into that remarkable mind; nothing was forgotten, nothing was useless. Muralitharan is the man who remembers everything

Every ball, every wicket was tucked away into that remarkable mind; nothing was forgotten, nothing was useless. Muralitharan is the man who remembers everything

|

Sri Lanka have won 50 Test matches in all. Muralitharan has played significant

roles

in 45 of them, claiming 373 wickets at 15.19, taking five-fors an incredible 36 times. He might have finished with the best-ever figures for a single innings, but after he had claimed nine wickets against Zimbabwe

at Kandy, Russel Arnold dropped a catch at short leg. Then, while bowlers at the other end tried desperately not to take a wicket, Chaminda Vaas accidentally had the last man caught behind amid stifled appeals. Murali has taken ten in a match four games in a row. Twice.

That record alone would have ensured Murali a place in the pantheon. But his influence is not restricted to his country's improved performance. With better bats, shorter boundaries, and tougher physiques, batsmen have threatened to eliminate the offspinner from the game. Murali has kept the craft alive with a simple ploy - being successful at it. By developing the doosra that was invented by Saqlain Mushtaq, he widened its scope. I have seen Sachin Tendulkar read the doosra correctly, and still succumb to it. This is what makes Murali special.

He also showed the gap that exists between visual perception and scientific precision by demonstrating for the cameras the legality of his bowling action. It led to a more precise definition by the ICC. Changing the rules of the game is clearly a Muralitharan specialty.

Cricket, like most sports, often thrusts greatness upon the merely good. Sometimes

the highest aggregate in batting or bowling, for example, or the record for the highest individual score, is held by a player - however briefly - who doesn't belong at the high table. When Matthew Hayden, for instance, made 380 to top the list of highest individual scores, the passionate prayed that either Brian Lara or Tendulkar would soon relieve him of the record and restore the natural order of things. Lara obliged. Likewise when Courtney Walsh, with 519 wickets, headed the bowlers' tally, the prayer was for a Muralitharan or a Shane Warne to take over. Murali did so, three years ago, and now he is, quite properly, reclaiming the record that belongs to him by virtue of his skill, his longevity, his impact, his record as the finest bowler of this or any other age. God's in his heaven, we might say, and all's right with the world.

Suresh Menon is a writer based in Bangalore