Stuart Clark and

Steve Harmison have shared much in common of late. In form and out of favour, both fast bowlers have lurched between resignation and despair during the past month as their compelling bids for selection have failed to sway the respective powers that be.

Harmison's omissions were perhaps understandable given the spin-friendly conditions in Cardiff, and the strong performance of England's seamers at Lord's. As impressive as his 53 wickets for Durham and England Lions have been this year, Harmison still carries with him the baggage of meltdowns past; a burden his Durham team-mate, Graham Onions, does not possess.

The cold-shoulder treatment afforded to Clark has been altogether more mystifying. At Lord's and again at Edgbaston, Australia's bowlers struggled to create periods of sustained pressure, due largely to the errant ways of Mitchell Johnson and Peter Siddle. Most observers equated that to a Clark-shaped hole in the Australian attack. Selectors felt otherwise.

The argument against Clark was one of balance. Team management insisted that Mitchell Johnson, Peter Siddle and Ben Hilfenhaus warranted retention after their triumphant effort in South Africa, with Nathan Hauritz, the sole spinner, on hand to provide variation. That came as cold comfort to Clark who, despite offering the pressure-building accuracy so desperately required, could not be accommodated in an inflexible selection climate.

So it was on Friday that both Clark and Harmison found themselves back in the favour of their teams, albeit for vastly different reasons. Harmison was called in to replace Andrew Flintoff, England's attack leader, who finally succumbed to a knee injury after a month of painful defiance. Clark, meanwhile, was a first-choice selection in an all-pace line-up charged with the task of taking the 20 wickets that had eluded Australia in Cardiff, London and Birmingham.

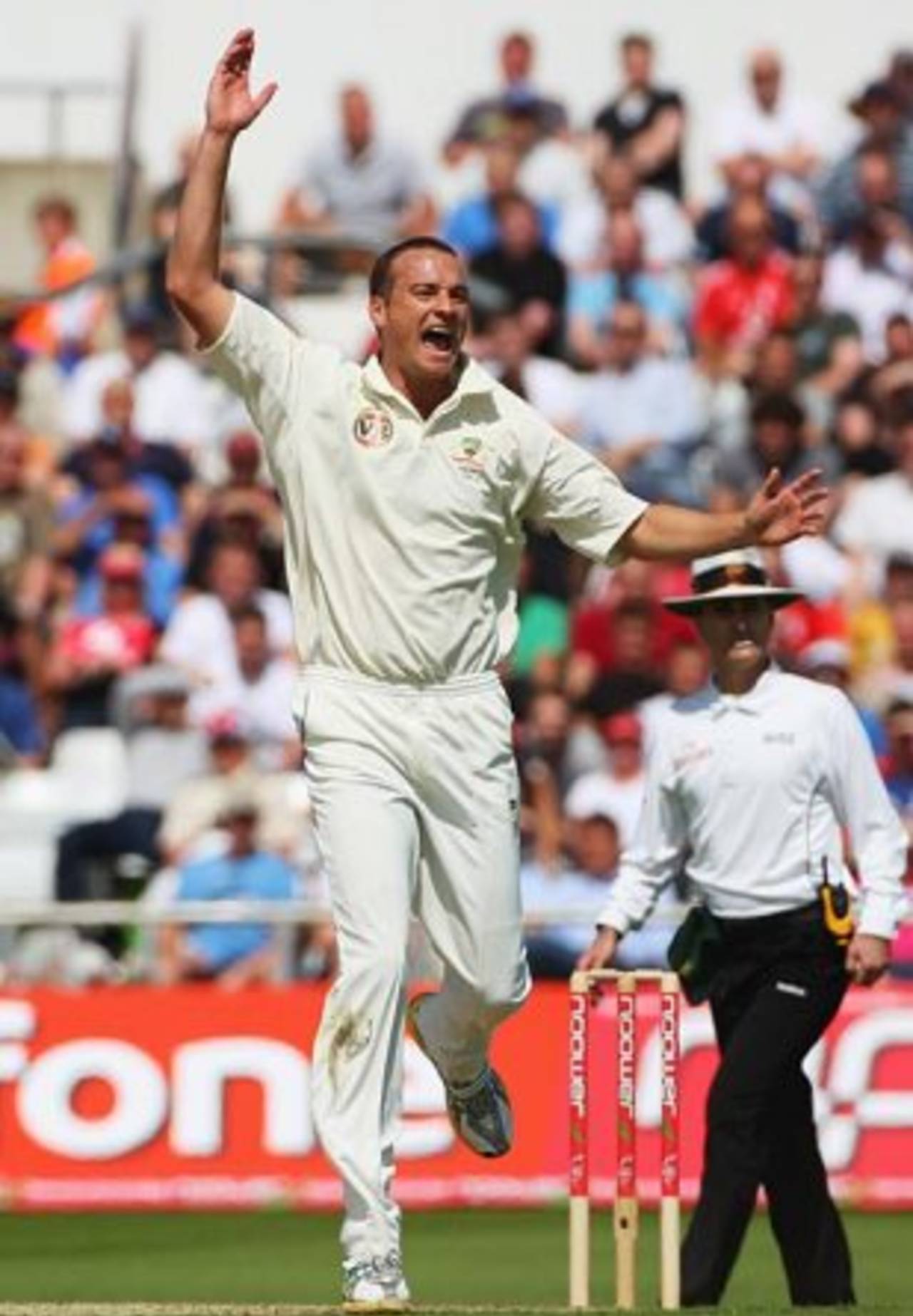

Clark fired from the outset, looking astonishingly comfortable for a man returning to Test cricket after a nine-month absence. The asphyxiating combination of deliberate line and full length denied England even a single until the penultimate ball of his third over. And when Paul Collingwood fell four deliveries later, pushing at an away-swinger, Clark's three Tests of Ashes isolation appeared all the more befuddling.

Clark followed with the wickets of Alastair Cook and Stuart Broad, but as significant as the steady stream of departing batsmen at his end was the influence he was exerting at the other. For one of the rare times this Ashes series, the Australians bowled in partnerships, and Johnson capitalised on the pressure Clark built throughout his ten over spell of 3-18. His over all Test record against England now stands at 29 wickets at 15.89 in five-and-a-half Tests. A steward's enquiry will be launched if he does not play at The Oval.

Harmison, alas, was not so prosperous. After the first four balls of his opening spell, Australia had amassed almost 10% of England's first-innings total - a statistic that, in fairness, said more about the hosts' timid batting than it did Harmison's bowling. He rallied with the wicket of Simon Katich, fending off a rising delivery to short backward-square, only to struggle thereafter in the face of a thunderous Ricky Ponting onslaught.

Suddenly, the bad old Harmy - the concede-a-boundary-and-spin-on-your-heels Harmy - had returned. Shoulders slumped further with each Ponting pull and Shane Watson cut, never more so than when the Australian duo blasted a succession of half-trackers for 22-runs in a dire two-over second spell.

The importance of this passage could not be overstated. Defending a paltry total, England could ill-afford any form of inaccuracy if they were to remain in the contest, least of all from the man who inherited the enforcer tag after James Anderson injured his leg while batting. Not even a brutal final spell, in which he rattled Michael Clarke with a brutal bouncer, could make ammends for his earlier errancy. The Australians were already off the hook.

Alex Brown is deputy editor of Cricinfo