Yesterday my son, who is fifteen, said: “ Last year we had a great team.” I was about to set him right, to say that it was nearly three years ago, in 2004, that we’d had something approaching a great team when Ganguly’s Goers had nearly beaten Waugh’s Invincibles in Oz, when he resumed his sentence: “…then Bergkamp and Viera left.” I felt a goose walk over Indian cricket’s grave.

Most of my son’s classmates find greater pleasure in watching Thierry Henry, a Frenchman who captains a London club, Arsenal, than in watching Rahul Dravid turn out for India. The boys in his class who aren’t fixated on Arsenal are obsessed with Manchester United and someone called Rooney who looks worryingly like an Eighties model skinhead. I could be wrong, my sample could be too small, but I think we’re seeing a shift in the sporting culture of metropolitan Indian schoolboys of a particular class. They’re seceding from international cricket and offering their enthusiasm and loyalty to English league football.

Before you go off thinking that my son’s school is some deracinated, air-conditioned NRI heaven, let me assure you that it’s not. Sardar Patel Vidyalaya is an austere, emphatically desi school, with a great cricket tradition. It has produced Indian internationals (Ajay Jadeja, Murali Karthik) and it has one of the most powerful cricket teams amongst Delhi’s schools. Lots of sensible kids in the school aspire to play competitive cricket. So far, so good. But ask any parent with a boy in middle-school and he’ll tell you the same thing: cricket’s reasonably popular, but it isn’t cool.

No, watching Arsenal play Chelsea with your friends is cool. Watching Arsenal play Chelsea wearing the red, obscenely priced Arsenal jersey, is cooler. To fold yourself into Arsenal’s global fan base with a casual ‘we’ is coolest of all, because that’s the very acme of cosmopolitan belonging.

That ‘we’ wouldn’t have been possible till a few years ago, before Star/ESPN began telecasting fixtures live. Recorded matches can seem second-hand because others have watched/used them already. With live telecasts beamed in by satellite, a schoolboy in Delhi can own the action of the match, its suspense, its exhilaration, its heartbreak, in the same way as someone in South Harrow can, because both of them see it happen in real time. Paradoxically, supporting league football is easy because it doesn’t involve treason. It’s not England you’re supporting at football where once you supported India at cricket. No, in cheering for Arsenal you’re supporting a club side whose captain is French, and whose players are as likely to come from Cote d’Ivoire as Camden Town.

And why is Arsenal more compelling than India? Two reasons. One, the Indian team isn’t successful enough at cricket to be glamorous. The last ten years of Australian dominance have left the other cricketing nations looking like pygmies squabbling for second place. Two, with the decline of the West Indies and the less than competitive presence of Zimbabwe and Bangladesh, international cricket sometimes seems like a tawdry, post-colonial leftover, too small and tarnished a mirror to reflect the growing self-consequence of contemporary India’s globalizing elite. The extraordinary celebration of Bhaichung Bhutia, an Indian footballer who was recruited to play for a third division English club, is a forewarning of the enormous enthusiasm that’s likely to be stirred up if one or two Indian players manage to make their way into the upper reaches of a truly global league like the English Premiership.

I tell myself that even if my son’s class is representative of its kind in India’s great cities, we’re still talking about a small minority of Indian cricket’s viewership. As television-aided cricket reaches more deeply and widely into Indian society, as talent begins to be produced in provincial places (think of Virendra Sehwag, Irfan Pathan, Munaf Patel, and Mohammad Kaif), metropolitan towns like Bombay, Delhi, Bangalore and Madras become less important as nurseries of talent, and urban, middle-class, English-speaking children become a diminishing sliver of Indian cricket’s huge installed fan base.

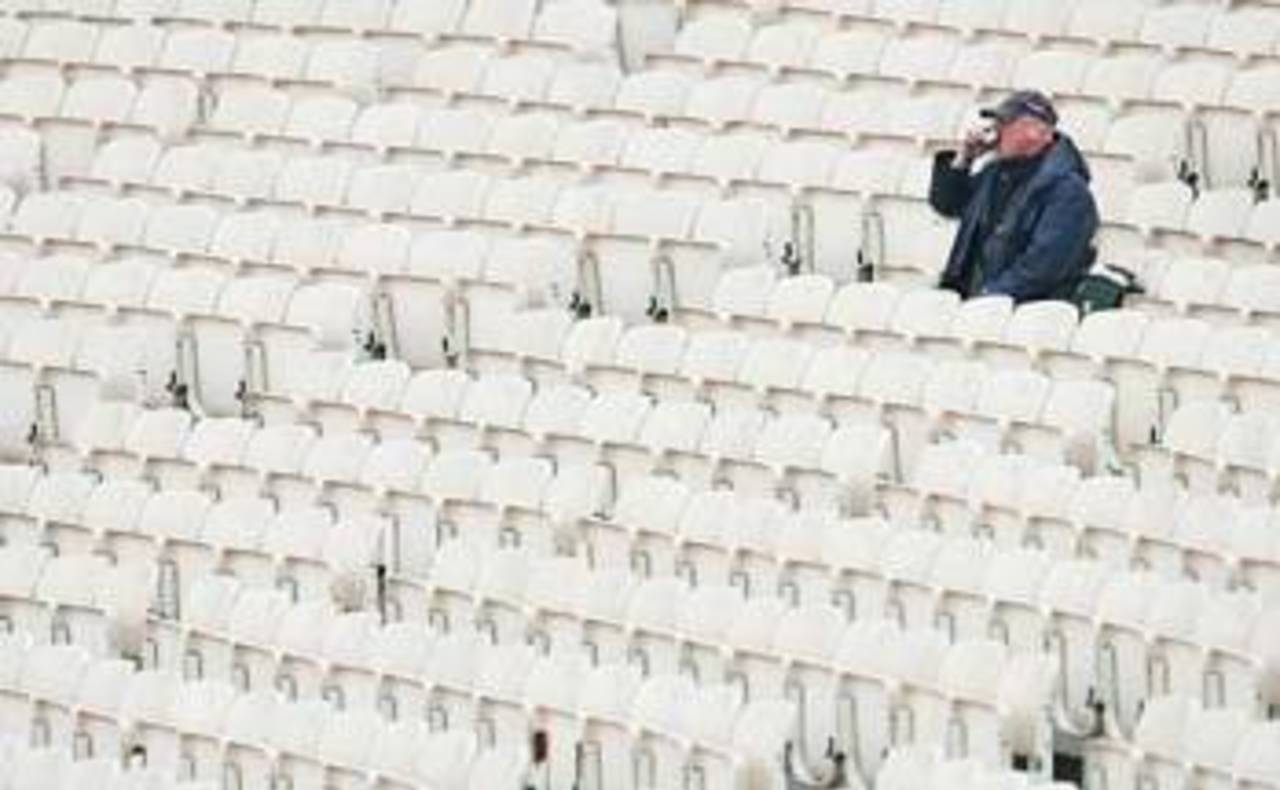

But I’m not consoled. Our cricketing genes need to reproduce themselves. When our children defect, an unbroken sequence of cricketing generations is severed, a familial cricketing tradition, a silsila, becomes defunct. Less sentimentally, no Indian game can afford to lose the children of the haute salariat, the class of people who buy fridges and washing machines. Once upon a time Test cricket was one of the white goods that this class consumed reflexively: but for how much longer?

A longer version of this post published in The Telegraph, Kolkata, is available here Mukul Kesavan is a writer based in New Delhi